Using specimens from the museum's scientific collections, Dr. Nancy Moncrief, Curator of Mammalogy at VMNH, worked with Dr. R. Jory Brinkerhoff, Associate Professor of Biology at the University of Richmond, and other colleagues to study the mice and the diseases they carried. Their study, titled Use of mammalian museum specimens to test hypotheses about the geographic expansion of Lyme disease in the southeastern United States, was published by ScienceDirect in November 2022. This page includes details about the study, including a link to the technical article regarding the research.

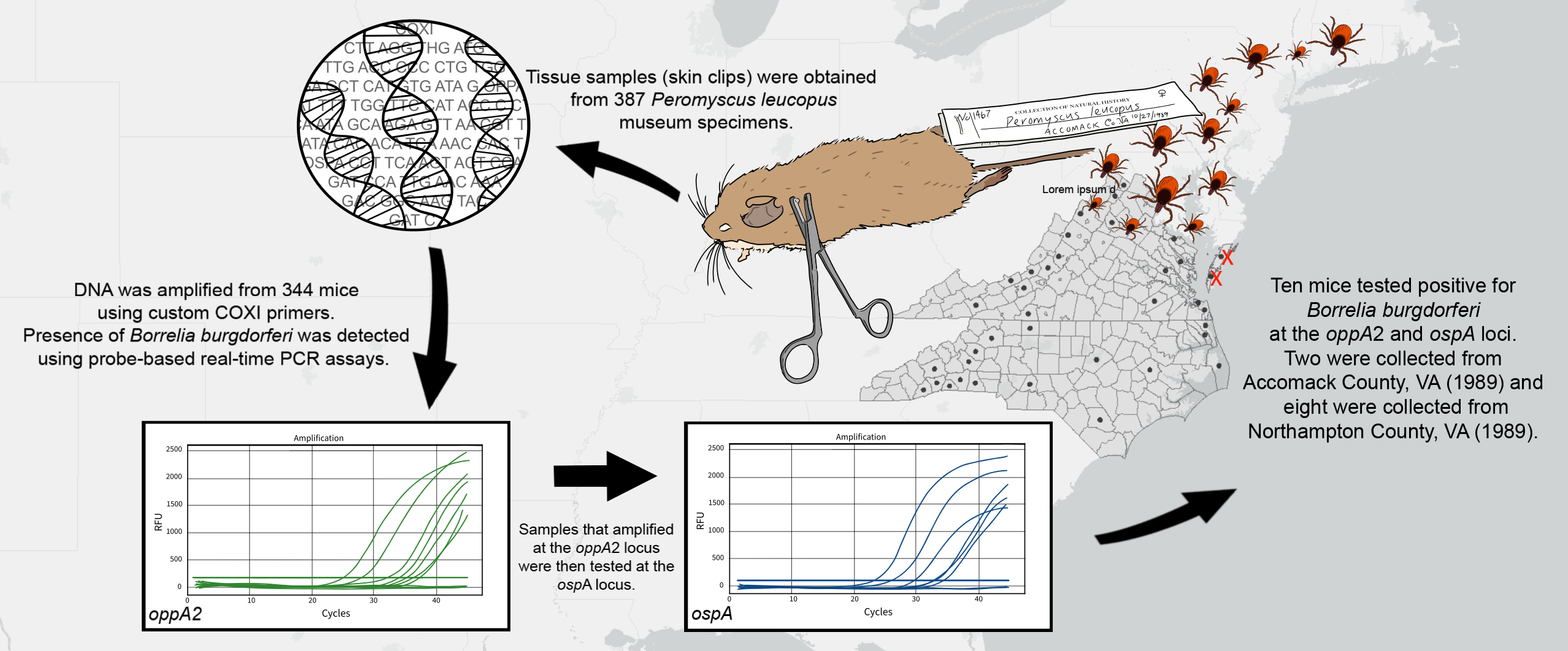

Below is a graphical abstract of their research.

Graphic: Meghan Leber

Graphic: Meghan Leber

Dr. Brinkerhoff is an expert in the field of diseases that ticks transmit when they bite a human to feed on their blood. Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium called Borellia burgdorferi, which is transmitted by the black-legged tick, Ixodes scapularis. One of the black-legged tick's most popular targets is the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus). In fact, nearly all white-footed mice are infected in the places where Lyme disease is common.

Historically, Lyme disease has been concentrated in the northeast and north-central United States, but its range is expanding southwards into Virginia and North Carolina. The first report of Lyme in eastern Virginia occurred in 1990, but there are now more and more cases in the mountainous parts of western Virginia and North Carolina. Dr. Brinkerhoff wanted to know why.

One hypothesis was that black-legged ticks and the animals they infect have expanded their ranges southward along the Appalachian Mountains. A second hypothesis was that the Lyme disease bacterium was already present in this area, infecting a variety of animals such as the white-footed mouse, but not humans. To test the hypotheses, Dr. Brinkerhoff needed to look for the Lyme disease bacterium in white-footed mice that lived in Virginia and North Carolina before the rapid rise in the number of western cases. That's where the VMNH collections come in!

Dr. Brinkerhoff contacted Dr. Moncrief and Ms. Lisa Gatens, the Collections Manager of Mammalogy at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. These two museums have thousands of specimens, preserved as dried skins and skeletons, from native mammals, including many from the white-footed mouse. Some of them were collected and placed in storage more than a hundred years ago!

Dr. Moncrief and Ms. Gatens supplied tiny pieces of the ears of white-footed mouse specimens collected before the year 2000. Dr. Brinkerhoff and his students tested the samples to try to find DNA from the Lyme disease bacterium. They did find the bacterial DNA in mice from eastern Virginia, but the western mice showed no trace of the same DNA. That supports the second hypothesis: that the western cases of Lyme disease are the result of the rapid southward range expansion of infected ticks and the animals they feed on.

As with all science, big questions remain. One of the biggest is “what caused the black-legged ticks to expand into to the south?” The answers to these questions just might be found in specimens of ticks or other animals currently stored in our museum's cabinets!

Hours & Admissions

Hours & Admissions Directions

Directions