September 14, 2021

Ben here with the Tuesday edition of #BenInNature presented by our friends at Carter Bank & Trust!

Here's a critter that you won't find in southwest Virginia -- at least, you won't find it here yet, but you'll likely be seeing it before too long. This is Lycorma delicatula, better known as the spotted lanternfly!

Over the weekend I drove up to Charles Town, West Virginia on an important museum-related mission (all right, I was getting a pinball machine, but I can multitask). On the way back, I stopped to grab a sandwich in Winchester, Virginia and discovered the parking lot was crawling with spotted lanternflies! So why is this a big deal?

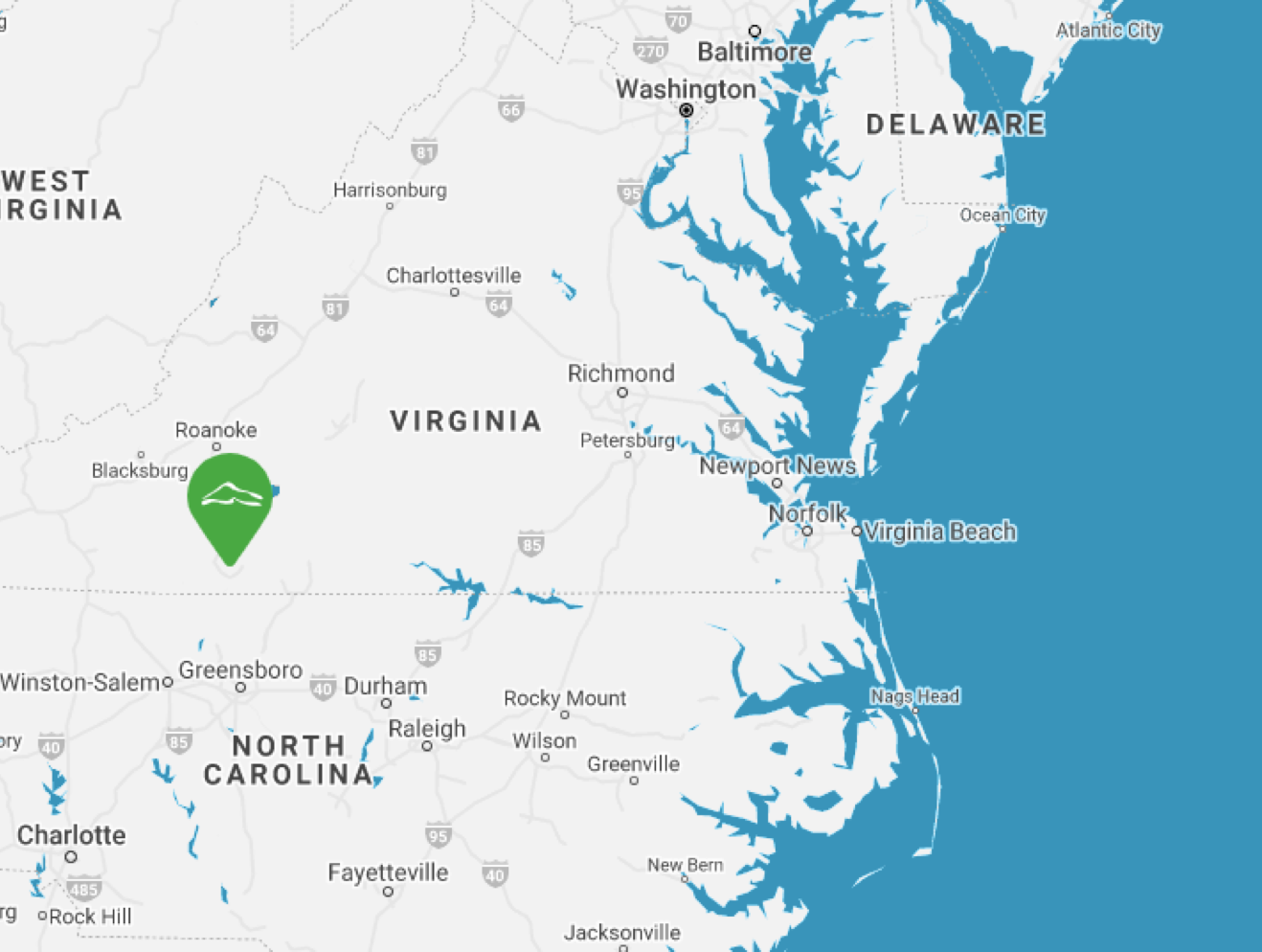

The spotted lanternfly is native to southeast Asia, but it has spread to Japan, South Korea, and the U.S. It only arrived here in 2014, but it has spread aggressively since then. As of now, spotted lanternflies are established in parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, New York, Connecticut, Ohio, West Virginia, and northern Virginia. They were first found in Berks County, Pennsylvania six years ago, where they were believed to have arrived as egg masses in a shipment of stone a couple years earlier. They have been aggressively expanding their range ever since.

Why is that bad? Spotted lanternflies are large planthoppers that drink fluids from plants, and their preferred host is Ailanthus altissima, also known as the tree of heaven. Ailanthus is also an invasive species in the U.S., so at first it might seem like the problem should solve itself. Unfortunately, the spotted lanternfly isn't all that picky, and it will also feed on grape vines, fruit trees, apple trees, stone fruit trees, ornamental trees, and even common forest trees such as walnut, birch, and maple. While feeding, spotted lanternflies excrete a sugary waste product that encourages mold growth, which means they can occasionally kill trees just by allowing mold to proliferate on the tree.

Clearly, this is bad news for the delicate natural balance, and it's also bad news for agricultural industries. There are a few different methods being employed to slow the spread of lanternflies. One method is culling Ailanthus trees and leaving only a few male trees, as the spotted lanternfly requires a meal from this tree before it can lay eggs. The unculled trees are covered in sticky bands and used as trap trees to catch any nymphs. Infested trees have also been sprayed with pesticides, and people have attempted to kill lanternfly eggs by scraping them into bags of rubbing alcohol or hand sanitizer.

Realistically, while we might be able to slow the spread of the spotted lanternfly, it's unlikely this species will be eradicated in the U.S. They're likely here to stay, and it will be up to us to mitigate their damage as best we can.

If you're in Virginia and find a spotted lanternfly outside of its current established range, contact the Virginia Cooperative Extension at the following link: https://vce.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_0fdsQXRg8TO8uzk

ABOUT #BenInNature

Social distancing can be difficult, but it presents a great opportunity to become reacquainted with nature. In this series of posts, Administrator of Science Ben Williams ventures outdoors to record a snapshot of the unique sights that can be found in the natural world. New updates are posted Monday - Friday, with previous posts highlighted on the weekends. This series of posts is made possible thanks to the support of VMNH Corporate Partner Carter Bank & Trust (www.cbtcares.com).

NATURE PHOTO IDENTIFICATIONS

If you discover something in nature that you would like help identifying, be sure to message us right here on Facebook with a picture (please include location and date of picture) and we'll have our experts help you identify it!

Hours & Admissions

Hours & Admissions Directions

Directions